Late Beethoven

February 12, 2025

By: Noel Morris ©️2025

Beethoven’s last decade is as much a psychological journey as a musical one. For sure, the audacity and experimentation that defined his “heroic decade” fed into his later works. But he suffered a dry spell and emerged a more introspective and philosophical composer.

As he inched toward his forty-third birthday, he'd completed eight symphonies, five piano concertos, and trunkloads of chamber works. His Seventh Symphony drew applause that “rose to the point of ecstasy.” But privately, he felt the ground shifting beneath his feet.

Napoleon, the so-called great liberator, faltered along with Beethoven’s hopes for freedom and universal brotherhood. The Austrian emperor reasserted his iron grip. Beethoven’s circle of benefactors dwindled, and his hearing grew worse. On top of that, documents point to a failed romance. (We know little about the woman he called his “Immortal Beloved.”)

Between 1813 and early 1815, he banged out a series of crowdpleasers, boosting his popularity around Vienna while offering little for posterity. Biographer Maynard Solomon wrote: “These works, filled with bombastic rhetoric and ‘patriotic’ excesses, mark the nadir of Beethoven’s artistic career.” And then, like a caterpillar, he went dormant.

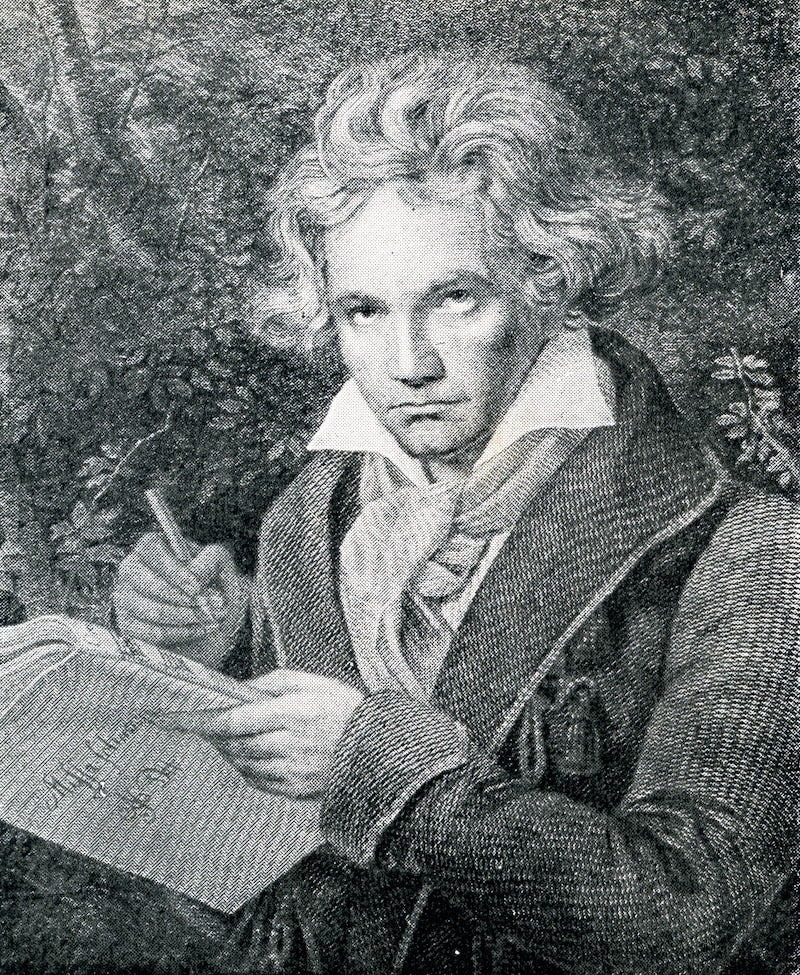

Now clinically deaf and chronically ill, Beethoven gave his last public piano performance in January 1815. That same year, his brother Caspar Carl died, and Ludwig blundered through a five-year custody battle over his nephew. Music took a back seat to the unfortunate legal proceedings against the boy’s mother. Meanwhile, he let himself go; his hair grew matted and his clothes shabby. Necessarily, the outside world communicated with him via pen and paper. Lubricating himself with bottles of wine, he shared laughs with his friends and railed against the Emperor. (The secret police ignored him because he was a famous composer and seemed a little touched in the head.)

Beethoven re-emerged as a composer in 1818 to write his colossal Hammerklavier Sonata. Music critic Harry Haskell notes the Sonata’s “sharp dynamic contrasts, sudden shifts of register and texture, and bold juxtapositions of keys.” From this point on, Beethoven is at one with his imagination; he’s unfettered by the hearing world's distractions, conventions, and demands. Sharp contrasts and bold juxtapositions became his vocabulary for pushing his late works into a realm of their own.